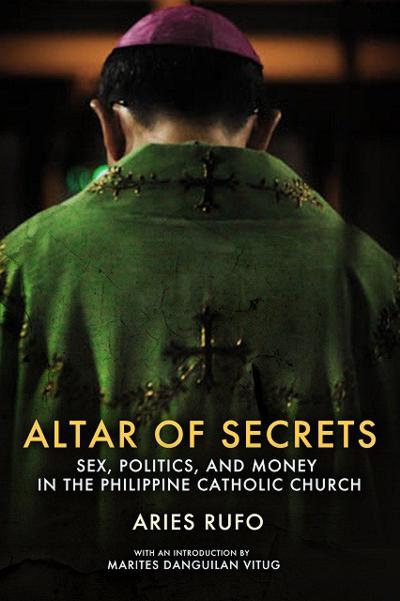

Book Review: Altar of Secrets: Sex, Politics, and Money in the Philippine Catholic Church (by Aries C. Rufo)

Main Article Content

Abstract

Publisher: Journal for Nation Building Foundation, Manila, 2013

Publication Date: 2013

Language: English

ISBN 13: 9789719568902

Aries C. Rufo’s Altar of Secrets is an investigative work that exposes the systemic moral and institutional failings of the Roman Catholic Church in the Philippines. The book presents a profoundly unsettling narrative of Cleric’s/Priest’s misconduct, financial corruption, and political collusion, challenging the moral and theological authority of one of the most influential institutions in the Philippines. An experienced journalist, Rufo navigates the Church’s impenetrable walls of secrecy to reveal its contradictions: an institution that preaches morality while often failing to hold itself accountable for transgressions within its ranks and by giving light consequences to the violators.

Rufo opens the book with a searing critique of the Catholic Church’s handling of clerical sexual misconduct, highlighting cases involving high-ranking clergy. From bishops fathering children to priests engaging in illicit relationships, Rufo paints a vivid picture of an institution riddled with scandal. He highlights the Church’s practice of quietly reassigning offending priests to other dioceses or encouraging them to retire, thereby avoiding public scrutiny.

One of the most shocking revelations is the Church’s tacit acceptance of a “quota system,” which permits priests to remain in ministry after fathering a single child but mandates their removal if they have more than one. Rufo’s documentation of these practices underscores a systemic disregard for accountability and victim welfare, particularly in the context of abuse cases. The code of silence, or omertà, perpetuates a culture where transgressions are normalized, as Church leaders prioritize institutional reputation over justice for victims (Rufo, 2013).

This raises profound questions about the Church’s claim to moral authority. As Rufo notes, the Church demands high moral standards from the laity while excusing its clergy from similar accountability, eroding trust in its moral leadership. This is particularly troubling given the priestly vow of celibacy, which symbolizes complete devotion to God, and the understanding of priesthood as the Alter Christus (Other Christ), a sacred calling rather than merely a profession. Such inconsistencies undermine the very essence of the priesthood’s spiritual and moral exemplariness.

The book also delves into the Church’s financial affairs, revealing mismanagement, embezzlement, and opaque handling of donations. Rufo characterizes diocesan hierarchies as modern-day feudal estates, where bishops wield unchecked authority over Church finances. He recounts the collapse of Church-run banks, such as Monte de Piedad, due to financial mismanagement and details how donations meant for charitable purposes were siphoned off for personal gain.

Rufo’s analysis demonstrates how these practices contradict the Church’s professed mission to serve the poor. By exposing the lack of financial accountability, he challenges the Church’s credibility in demanding transparency and ethical conduct from political leaders. This hypocrisy undermines the Church’s prophetic role in advocating social justice and its theological commitment to the “preferential option for the poor” (Rufo, 2013). These contradictions echo the realities of the Catholic Church in the time of Rizal, as vividly portrayed in his novels Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo. While not considered strictly factual, these works highlight abuses of power, corruption, and moral decadence within the Church hierarchy, which remain common knowledge and resonate with modern critiques. Such parallels deepen the gravity of Rufo’s argument, illustrating how historical and systemic inconsistencies continue to erode trust in the Church’s moral authority.

In perhaps the book’s most controversial section, Rufo examines the Church’s deep involvement in Philippine politics. He describes how Church leaders maintained close relationships with political figures, often receiving material favors in exchange for their support. For example, Rufo recounts how former President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo cultivated relationships with bishops by providing financial largesse, even amid corruption scandals that plagued her administration.

Rufo’s critique is particularly sharp in discussing the Church’s opposition to the Reproductive Health Bill. The Church’s vehement campaign against the bill exemplifies its willingness to impose its moral views on state policies, often disregarding the secular nature of governance. Rufo argues that this overreach into political affairs not only undermines democracy but also alienates segments of the population who feel the Church prioritizes its institutional interests over the common good (Rufo, 2013).

Rufo’s exposé invites reflection on the nature of institutional power and its capacity to corrupt. Drawing on Michel Foucault’s theory of power, the book illustrates how the Church’s hierarchical structure enables a concentration of authority that is resistant to external scrutiny. This unchecked power fosters an environment where abuse and corruption can thrive. The Church’s reliance on secrecy and its resistance to reform reflect what Foucault might describe as a strategy to maintain control over its members and public image (Foucault, 1977). Further, by shielding errant clergy from scrutiny, the Church prioritizes self-preservation over moral integrity, which undermines its claims to spiritual leadership (Foucault, 1977).

This hypocrisy resonates with Friedrich Nietzsche’s critique of moral institutions. Nietzsche argues that such entities often cloak their will to power in the guise of virtue, wielding moral authority as a tool of domination. Rufo’s critique exemplifies this dynamic, exposing an institution that demands moral rigor from others while excusing its own transgressions. The synthesis of Foucault’s and Nietzsche’s philosophies offers a sobering view of the Church as an institution where power and morality are in constant tension, often to the detriment of its mission.

However, the Local Church seems to have failed to learn from its past, as vividly chronicled in the works of Jose Rizal. Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo exposed the abuses of power, hypocrisy, and corruption in the Church during the colonial period – issues that were instrumental in igniting revolutionary fervor in the Philippines. The fact that similar dynamics persist today raises troubling questions: Why has the Church not internalized the lessons of its historical failings? Why does it continue to repeat the patterns that alienated the faithful in Rizal’s time?

From a theological perspective, Rufo’s revelations compel a reassessment of the Church’s understanding of sin and grace. The Church’s reluctance to publicly address clerical misconduct reflects an institutional failure to embody the Christian call to repentance and renewal. By shielding errant clergy from accountability, the Church undermines its mission to be a witness to Christ’s transformative grace.

The book challenges the Church to embrace a model of humility and transparency, as Christ exemplifies. This involves addressing individual failures and undertaking structural reforms to prevent future abuses. Rufo’s work thus aligns with liberation theology’s emphasis on institutional transformation as a necessary dimension of salvation (Gutierrez, 1973).

As a member of the Catholic Church, reading the Altar of Secrets evokes a mix of sorrow, anger, and hope. The book’s revelations challenge me to confront the dissonance between the Church’s divine mission and the human failures of its leadership. The institution that has shaped my faith and values now stands accused of betraying the very principles it professes to uphold. This dissonance compels a reexamination of my relationship with the Church, not as an unquestioning follower but as an engaged member who seeks accountability and reform.

The Catholic priesthood, understood as the Alter Christus (Other Christ), is a sacred vocation rooted in the eternal words Psalm 110:4, “You are a priest forever, in the line of Melchizedek.” These words remind us of the divine calling of priests to embody Christ’s love, humility, and sacrificial service. It is this profound spiritual identity that makes the moral failures of some clergy even more disheartening. The breach of trust not only undermines the Church’s moral authority but also distorts the image of the priesthood as a reflection of Christ’s eternal priesthood.

Despite the pain of these revelations, faith remains anchored in the Gospel’s core teachings rather than its messengers’ fallibility. Like all human institutions, the Church is susceptible to sin but also possesses the capacity for renewal. Rufo’s work is a reminder that the path to redemption requires confronting uncomfortable truths and working toward systemic change. As members of the Pilgrim Church – the Militant Church – believers are called to actively participate in its journey toward holiness. This means demanding transparency from Church leaders, supporting initiatives that align its actions with its spiritual mission, and ensuring that the priesthood truly reflects its divine calling. Ultimately, the mission of the Pilgrim Church is to uphold the Gospel’s call to love, justice, and humility, embodying Christ’s eternal presence in a world that desperately needs His light.

Altar of Secrets is more than an exposé of the Philippine Catholic Church; it is a call to action for both the clergy and the laity. Rufo underscores the urgent need for transparency, accountability, and reform within the Church. He challenges the institution to align its practices with its professed values, thereby restoring its credibility and moral authority. Philosophically, the book compels a reconsideration of the relationship between power and morality in religious institutions. Theologically, it invites the Church to rediscover its prophetic mission, embracing the principles of justice, humility, and truth. As Rufo demonstrates, the Church’s ability to address its failures will determine its relevance in contemporary society and its faithfulness to the Gospel. In the end, Altar of Secrets is a courageous work that illuminates the darkness within a powerful institution, offering a glimmer of hope for transformation. Rufo’s insights resonate beyond the Philippine context, serving as a reminder that no institution – however sacred – should be exempt from scrutiny.

Downloads

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

References

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Pantheon Books.

Gutierrez, G. (1973). A Theology of Liberation: History, Politics, and Salvation. Orbis Books.

Rufo, A. C. (2013). Altar of Secrets: Sex, Politics, and Money in the Philippine Catholic Church. Manila: Journalism for Nation Building Foundation.